This post was originally published on this site

The number of companies withdrawing or declining to provide earnings guidance continues to grow, with Abbott, ConocoPhillips, Jack in the Box, GoPro, and Bed Bath & Beyond in just the last couple days.

JPMorgan, in a note to clients, said that so far 86 S&P 500 companies have suspended earnings guidance.

Not surprisingly, some in the corporate world are seizing on this canceled guidance to renew calls to kill the practice altogether.

“It’s a step in the right direction that such a large number of companies have opted to suspend guidance, regardless of the circumstances that caused them to arrive at that decision,” Sarah Keohane Williamson, CEO of FCLT Global, said in an editorial this week in Investor Relations magazine.

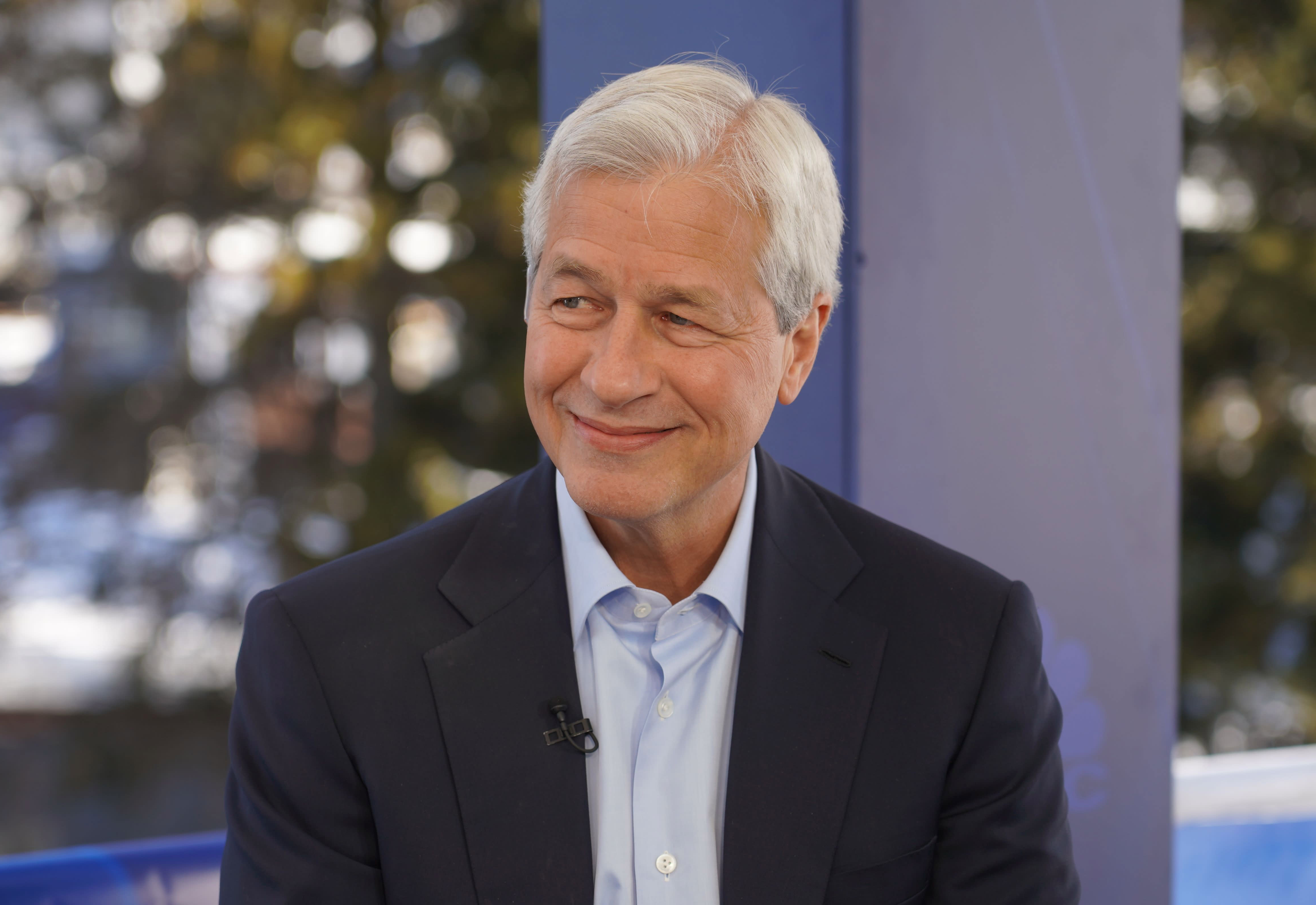

Two years ago Jamie Dimon and Warren Buffett called for companies to stop providing quarterly earnings guidance, arguing that it promoted short-term thinking.

Citing a 2015 Harvard study, Williamson said companies that emphasize quarterly earnings guidance get “the investors they deserve. Focusing on short-term metrics attracts transient, short-term shareholders, ultimately increasing share price volatility. It is linked to lower earnings growth, a higher cost of capital and a lower return on equity when compared with peers that issue guidance with a long-term orientation.”

Williamson also said investors don’t want this type of guidance: “In repeated surveys of the buy side, earnings guidance given for periods of less than one year was consistently deemed irrelevant in evaluating a company’s future prospects,” she wrote.

Sounds like a bit of a rant, but FCLT Global has clout. It’s a not-for-profit organization founded to encourage a longer-term focus in business and investment decision-making. Its members include BlackRock, Bridgewater Associates, Carlyle Group, Fidelity Investments, HSBC, Nasdaq, Cisco and Walmart.

This is not a new issue. Two years ago, JPMorgan’s Dimon, then chairman of the Business Roundtable, said the group of CEOs had endorsed backing away from providing quarterly guidance.

In June 2018, Dimon appeared on CNBC’s “Squawk Box” with Buffett, who also endorsed ending the practice. Quarterly guidance, Dimon told CNBC’s Becky Quick, can often put a company in a position where management from the CEO down feels obligated to deliver earnings and therefore may do things that they wouldn’t otherwise have done.”

The goal of providing a stable, long-term base of investors is certainly laudable. But is this a major issue? I’m not so sure. Here’s why:

- Not many companies do it. Only about 1 in 5 companies in the S&P 500 still provide quarterly guidance. It seems like there is more because the media tends to focus on those that miss and those that don’t.

- Even if all the companies eliminated quarterly earnings guidance, they would still be required by law to file quarterly earnings reports (10-Qs) with the Securities and Exchange Commission. An entire army of Wall Street strategists and analysts already provide commentary on future earnings trends based on these reports. If companies decline to provide commentary, Wall Street will certainly step into that vacuum. That means professional investors who have access to greater information will have an even greater advantage over the average investor. If companies don’t set goals, Wall Street will.

If you really want to promote long-term thinking, how about keeping management around a little longer? The time frame for CEOs remaining at firms is down to about five years, according to Jeffrey Sonnenfeld at Yale School of Management. These CEOs may have short-term thinking because, well, because they are short-termers.

“When you pay CEOs based on earnings, and the metric is quarterly earnings, and the compensation committee says 98% of your compensation is going to be based on the stock price, which investors have linked to the earnings, compensation drives behavior,” Scott Galloway of NYU’s Stern School of Business said on CNBC when Dimon made his remarks in 2018.

Finally, is it heretical to ask this question? What’s wrong with short-termism? Suppose I want to own a stock for a week, or a month, as a trade? I understand the company may not want to help me by providing guidance, but — and my apologies to Buffett for this — the idea that we are all going to kick back and own Coca-Cola for the rest of our lives is not very realistic.