This post was originally published on this site

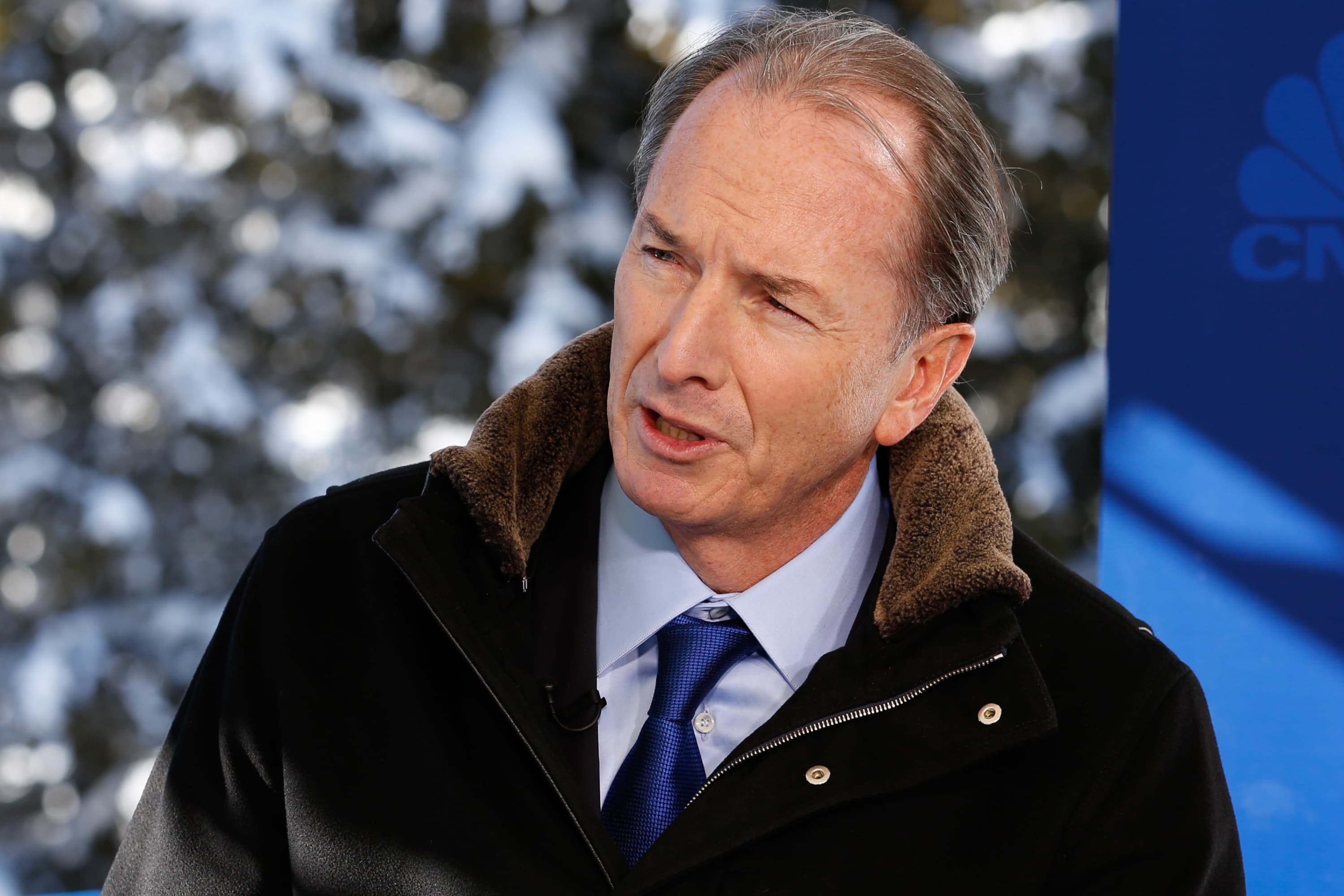

Morgan Stanley CEO James Gorman has just completed a pivot that began more than a decade ago.

With the announcement Thursday that Morgan Stanley is acquiring investment manager Eaton Vance for $7 billion, Gorman is adding heft and scale to the smallest of the New York-based bank’s three main businesses: the manufacturer of mutual funds and other investments.

It completes Morgan Stanley’s shift from being a firm dominated by traders and investment bankers to one where the more subdued and dependable management of money rules.

The bank began that journey in early 2009 when Morgan Stanley purchased Smith Barney from Citigroup in the throes of the financial crisis, gaining thousands of financial advisors in the process. This year, Gorman went a step further, announcing the $13 billion takeover of discount brokerage E-Trade to further its reach with the mass affluent.

Now, after $20 billion worth of recent deals, the bank will get well over half its revenue from fees related to wealth and investment management – owning a mutual fund factory with $1.2 trillion in assets and one of the world’s biggest armies of financial advisors to distribute them.

“We wanted to make sure that in very difficult times Morgan Stanley is steady in the water,” Gorman said Thursday in a call with analysts. “A decade ago, our asset management and wealth management businesses had bright spots in them, but they weren’t big enough, they weren’t at scale enough where they can provide real stability to the rest of the organization.”

When including its two recent acquisitions, Morgan Stanley would’ve generated $26 billion in wealth and investment management revenue in 2019, making it the biggest such company in the world by revenue, the bank says. All told, it will manage $4.4 trillion in client assets.

But investors have yet to recognize Morgan Stanley’s transformation, Gorman said.

“Our dear competitor Schwab, which is a great company, is I think trading at something like 20 times earnings at the moment,” Gorman vented. “And we’re trading as though we’re a pure trading business at about 9, 10 times earnings. It makes absolutely no sense.”

If his company traded at the midpoint between the two categories, at around 14 or 15 times earnings, “this stock would be $100” instead of its current level of about $49, Gorman said. “You’ve got to play the long game here.”

For Eaton Vance, a medium-sized player that specializes in actively managed funds, the deal relieves pressure that all asset managers not named Vanguard, BlackRock or Fidelity face. The shift to inexpensive passive investments has forced seismic changes throughout the industry.

“They are acquiring a good asset in a difficult industry,” said Devin Ryan, analyst at JMP Securities. “The only reason for a somewhat muted reaction today is that they’re paying what appears to be full price, and the near-term economics are modest in terms of moving the needle.”

Meanwhile, at Morgan Stanley’s rival Goldman Sachs, CEO David Solomon has been much more consumed by restructuring the businesses he already owns rather than buying new ones. The bank recently reshuffled the heads of his asset management and consumer and wealth management divisions.

Their focus may soon change to growing via acquisition, Ryan said. “Goldman Sachs aren’t precluded from doing things that are larger,” he said. “I wouldn’t be surprised if they went that route.”